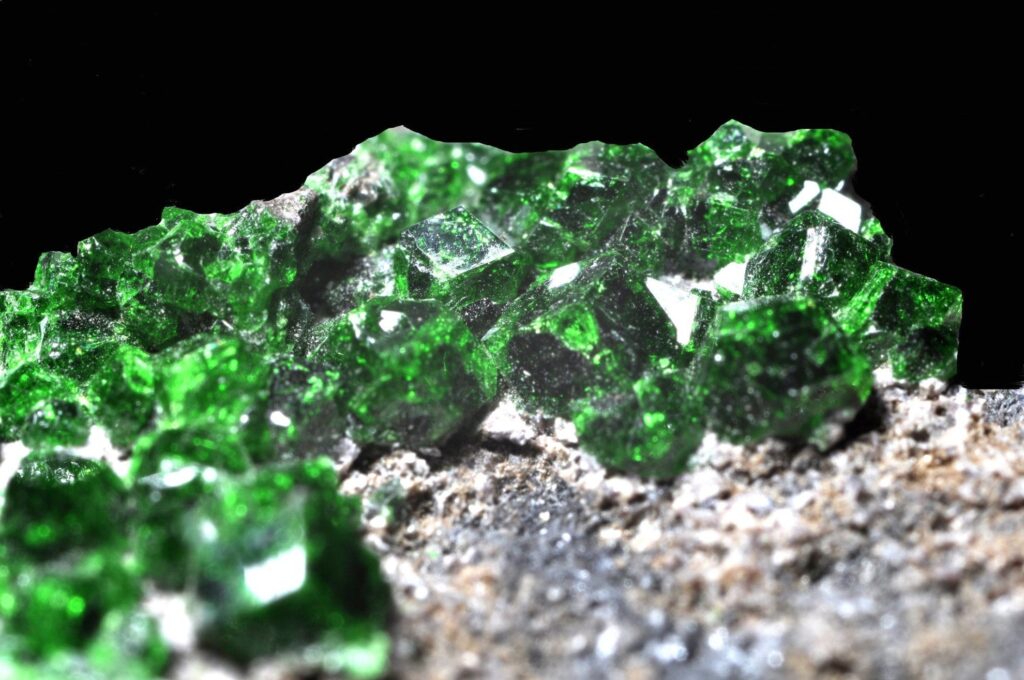

Dioptase is one of the most visually striking green gemstones in the mineral world. With its deep emerald-like color and brilliant crystal structure, it often surprises people who encounter it for the first time.Dioptase is a copper cyclosilicate mineral known for its vivid green to bluish-green color. Its intense coloration comes directly from its copper content. Chemically, it is composed of copper, silicon, oxygen, and hydrogen.Despite its emerald-like appearance, dioptase is a completely different mineral species. Its crystal system is trigonal, and it often forms transparent to translucent prismatic crystals with a glassy (vitreous) luster.

Because of its moderate hardness and perfect cleavage, dioptase is considered fragile compared to traditional jewelry stones.Dioptase is most commonly found in tiny crystal formations. While larger specimens do exist, they seldom contain broad, flawless sections, which means faceted stones typically weigh no more than one or two carats. Its perfect cleavage further complicates the cutting process, making faceting especially challenging. That said, skilled lapidaries can still shape attractive, larger cabochons from translucent masses of dioptase.

The Historical “Identity Crisis”

For centuries, dioptase was misidentified. In the late 1700s, it was famously sent to Tsar Alexander I of Russia as “emerald” from Kazakhstan. It wasn’t until 1797 that French mineralogist René Just Haüy identified it as a distinct mineral, noting its lower hardness and higher specific gravity compared to true beryl (emerald).

Dioptase is often compared to emerald because of its similar green color. However, they are very different minerals.

Advanced Identification Tips

The Pyroelectric Effect: One of dioptase’s most fascinating traits is that it is pyroelectric—when heated, the crystal generates an electric charge.

Visual Inclusions: Under a loupe, you may see “incipient cleavages”—tiny internal flat planes that reflect light, sometimes creating rainbow-like interference colors.

Streak Test: While a streak test (yielding a green-to-blue-green powder) is diagnostic, it is a destructive test and should never be performed on a finished gemstone.

Dioptase vs. Lookalikes

Dioptase is frequently confused with other green stones, but its unique physics give it away:

- Emerald: Much harder (7.5-8). Emerald crystals are typically hexagonal prisms, whereas dioptase is rhombohedral.

- Malachite: Usually opaque with distinct banding. Dioptase is transparent to translucent.

- Uvarovite (Green Garnet): Garnets lack dioptase’s perfect cleavage and have a different crystal habit (usually dodecahedral).

Locality and Value

The Tsumeb Mine in Namibia stands as the undisputed “Gold Standard” of the mineral world; specimens from this legendary site are prized for their large, saturated emerald-green crystals that pop against a stark white calcite matrix, commanding the highest premiums. In contrast, Altyn-Tyube, Kazakhstan, holds prestige as the “type locality”—the site of the mineral’s original discovery—and remains a favorite for collectors who value historical significance and classic, deep-toned crystal clusters.

For those seeking aesthetic variety, Kaokoveld, Namibia, is renowned for its striking associations, often featuring dioptase crystals nestled within or perched atop clear quartz. Meanwhile, the United States (specifically Arizona) has carved out a niche in the “micromount” market; while the crystals here are rarely large, their geometric perfection and sharp terminations make them highly coveted by specialized collectors who appreciate beauty on a miniature scale.

Safety and Toxicity

Due to its high copper content, dioptase requires careful handling during the cutting and polishing phases, as its dust is technically toxic. Inhaling or accidentally ingesting fine dioptase particles can lead to acute health issues such as respiratory distress or vomiting, while long-term chronic exposure may result in serious liver and kidney damage. Consequently, lapidaries and faceters must take rigorous precautions, including wearing high-grade protective masks and ideally utilizing a glovebox to contain dust during the cutting, polishing, and cleaning processes. However, it is important to note that these risks are specific to the processing of the mineral; once the stone is in its finished form, either as a polished gem or a cabinet specimen, wearing or handling it poses no health hazards to the owner.

Care and Maintenance

As a hydrous mineral containing structural water, dioptase is exceptionally sensitive to environmental shifts, requiring meticulous care to preserve its brilliance. Owners should strictly avoid ultrasonic or steam cleaners, as the intense vibrations and thermal shock will almost certainly cause the fragile crystals to shatter. Chemical exposure is equally hazardous; dioptase is soluble in acids—meaning even common household vinegar can etch and dull its surface luster. For safe maintenance, use only lukewarm water and a very soft cloth for gentle cleaning. Furthermore, to prevent accidental scratching, always store dioptase separately from harder gemstones like topaz or diamonds, ensuring this delicate copper treasure remains pristine.

Due to cleavage and possible fractures, dioptases should only be cleaned with a soft brush, mild detergent, and warm water. Consult our gemstone jewelry cleaning guide for more care recommendations.