Celestite, also spelled celestine, is a naturally occurring form of strontium sulfate (SrSO₄) recognized for its often delicate sky‑blue color and crystalline beauty. The mineral’s name derives from the Latin coelestis, meaning “heavenly,” a reference to this characteristic hue. Scientifically, celestite is significant both as a major geological source of strontium and as an indicator mineral in sedimentary environments. Although attractive specimens are sometimes faceted or displayed by collectors, its physical properties limit its practical use in conventional jewelry.

Mineralogical Identity and Classification

Celestite belongs to the broader sulfate mineral group, sharing close affinities with barite (BaSO₄) and anglesite (PbSO₄). These minerals form a continuum in which the dominant cation transitions from strontium at the celestite endmember to barium in barite. All three crystallize in related structures within the orthorhombic crystal system, reflecting the shared geometry of the sulfate anion (SO₄²⁻) coordinated with different metal cations.

Chemically, celestite can exhibit limited solid‑solution behavior with barite and occasionally with other sulfates, depending on local chemistry during formation. This capacity for elemental substitution explains the mineral’s occurrence in varied geological settings and the range of colors observed in specimens.

Color and Variety

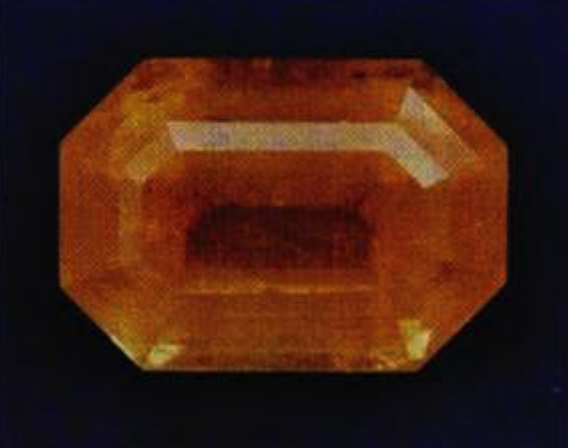

While many people are most familiar with celestite’s pale blue forms, the mineral can also present in a wider spectrum, including colorless, white, yellow, orange, and even rare reddish or greenish shades. These color variations are often due to trace elemental inclusions, slight structural imperfections, or fluid inclusions present during growth.

The classic sky‑blue specimens are most often associated with excellent transparency and contrast sharply with internal structural imperfections, making them visually appealing as collector pieces or occasional faceted gems.

Geological Formation and Occurrence

Sedimentary and Evaporite Settings

Celestite most commonly forms in evaporite deposits and sedimentary rocks, particularly dolomitic limestones and restricted basin environments where seawater or saline groundwater becomes concentrated through evaporation or diagenetic processes. In these settings, sulfate and strontium ions reach concentrations sufficient to precipitate celestite crystals within cavities, fractures, or pore spaces.

The mineral can also develop through diagenetic replacement, where strontium released during the breakdown of carbonate minerals interacts with sulfate in groundwater to form discrete celestite crystals.

Significant celestite localities include:

- Madagascar, particularly the Sakoany deposit, known for large and richly colored geodes.

- United States – Ohio (Crystal Cave), Michigan, Texas, and New York have yielded notable specimens.

- Other regions such as Canada (including rare orange crystals), Namibia, England, Italy, Egypt, Spain, and Tunisia.

These occurrences span diverse sedimentary and evaporitic basins, illustrating celestite’s broad geological distribution.

Geochemical Significance and Strontium Source

From a geochemical perspective, celestite is the primary natural source of strontium, an alkaline earth metal with applications in pyrotechnics, glass manufacture, and specialized ceramics. Strontium extracted from celestite is often converted into strontium carbonate or nitrate for industrial use.

In sedimentary geology, the presence of celestite within a rock sequence can serve as a proxy for past salinity conditions, fluid evolution, and basin restriction levels. Strontium isotope ratios in celestite also provide valuable data for reconstructing past seawater composition and correlating stratigraphic units over large distances.

Gemological Perspectives

Suitability as a Gemstone

While celestite’s delicate sky-blue hues and exceptional transparency can rival more prominent gemstones, its physical properties impose significant limitations on its use in conventional jewelry. With a Mohs hardness of only 3–3.5 and perfect cleavage in multiple directions, celestite is considerably more fragile than standard gem materials, rendering it highly susceptible to scratches and structural cleavage fractures. Consequently, faceted celestite remains a rarity, typically reserved for specialized collectors or museum displays rather than everyday wear. Furthermore, the mineral exhibits notable sensitivity to environmental factors; prolonged exposure to direct light can cause its “heavenly” blue color to fade, and temperatures exceeding 200°C can cause irreversible degradation of the stone’s structure.

Collector and Display Use

In the lapidary arts, celestite is most frequently fashioned into step cuts or emerald cuts to maximize weight retention and showcase its natural clarity. While the material’s inherent brittleness makes large faceted gems difficult to produce, exceptional museum-grade specimens can occasionally reach tens of carats, though most commercial cuts remain under three carats. Beyond the niche market for faceted stones, celestite is most prized in its natural mineral form. Large, crystal-lined geodes—particularly those sourced from Madagascar—are highly sought after for interior display and mineralogical collections due to their striking prismatic habits and vibrant coloration.

Care and Handling

Given its extreme fragility, celestite requires meticulous handling to prevent damage. Cleaning should be performed exclusively using a soft-bristled brush and mild detergent in lukewarm water, as harsh chemicals or ultrasonic cleaners can cause immediate fracturing. If the stone is incorporated into jewelry, protective settings such as bezels are essential to shield the edges from impact. Moreover, jewelers must exercise extreme caution during repairs, as the application of heat from a torch or exposure to intense workshop lighting can result in a permanent loss of color or thermal shock.

Comparison with Related Minerals

Celestite is often compared with other sulfate minerals:

- Barite (BaSO₄): structurally similar but typically denser and harder than celestite, with a broader range of industrial uses.

- Anglesite (PbSO₄): commonly forms in oxidation zones of lead deposits and has distinct geological context from celestite.

The gradational series between barite and celestite reflects how cation substitution affects mineral stability, form, and occurrence in nature.

Celestite is a multifaceted mineral that bridges sedimentary geology and gemology. Composed of strontium sulfate and crystallizing in the orthorhombic system, it offers insight into ancient evaporitic environments and the global mobility of strontium within the Earth’s crust. While its physical properties limit its use in conventional jewelry, its aesthetic appeal and rich scientific context make it a mineral of lasting interest to collectors and researchers alike.